Ignoring US white-collar crime will run up big tab

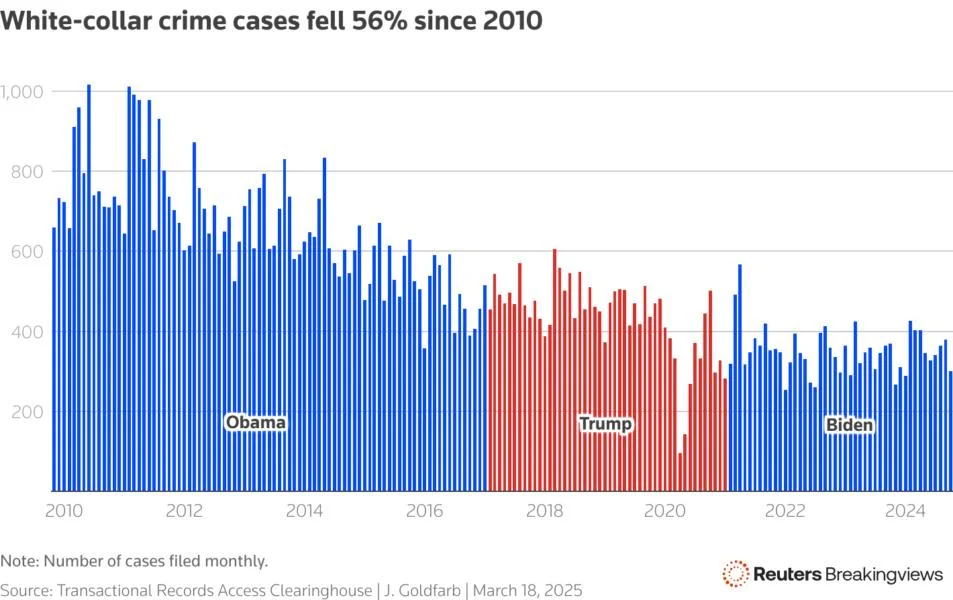

For a president who professes to be tough on crime, Donald Trump is clearing the way for a great deal of the white-collar variety. In a few short months, his administration has issued a startling sequence of proclamations to roll back U.S. enforcement of bribery, money laundering, tax avoidance, banking misdeeds, cryptocurrency abuse and other forms of corruption. Corporate compliance systems have been fortified over the past two decades but can withstand only so much pressure.It is perhaps no surprise that a plutocrat convicted of fraud over hush-money payments to a porn star and with six bankruptcies to his name would have a permissive approach to financial wrongdoing. Nevertheless, Trump’s desire to explicitly turn a blind eye to such forms of law-breaking is unprecedented in its collective haste and brazenness. His ostensible rationales are to unshackle U.S. businesses and make it easier for them to compete worldwide, to save taxpayers money, and to prioritize different threats such as illegal immigration and drug smuggling. The repercussions, however, will be extensive.Steering clear of government authorities is costly. The average U.S. company spends between 1% and 3% of its total wage bill to comply with the multitude of rules on the books, one recent study found. The National Association of Manufacturers separately put the figure at $13,000 per employee to keep up with federal regulations alone. Yet high standards contribute to the faith of investors in a system operating under the rule of law, lowering the cost of capital. Despite growing complaints about red tape, U.S. economic growth has been robust and stock prices until recently kept surging to new highs.Prosecutions of corporate and securities fraud, identity theft and other financially motivated misdeeds were already coming down. The number fell to about 4,000 cases in 2023, nearly half the figure for 2014, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. Despite this trend, there’s no shortage of swindling in the United States. Freshly released data from just a single agency, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, indicates that consumers reported losing $12.5 billion to fraud last year, a 25% increase from 2023. Nearly half of it was related to investment scams. The FTC was able to refund only a fraction, about $340 million, of the total.Trump’s executive orders and actions by billionaire Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency will drastically reduce oversight. The president said last month that enforcing the 48-year-old Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits bribery of overseas officials, hurts the competitiveness of U.S. companies and wastes prosecutorial resources. He halted new probes for six months, with rare exceptions, ordered a fresh review of all open cases and called for revised guidelines.Attorney General Pam Bondi has since refocused the Department of Justice on applying the FCPA to drug cartels and other international crime syndicates. She also shut down two teams dedicated to pursuing kleptocrats and seizing their assets, as well as a corporate enforcement unit designed to punish economic crimes related to national security and companies that evade sanctions and violate export controls.More broadly, the Treasury Department said it would essentially waive compliance with a law designed to curb money laundering by requiring clear disclosures about who exactly owns a U.S. company. Instead of an estimated 32 million businesses reporting such details, fewer than 12,000 would now be forced to comply each year.The Internal Revenue Service is drawing up plans to halve its roughly 90,000-person workforce, according to media reports. A tax-collecting department left with its smallest staff in seven decades will struggle to track avoiders and cheats, which may dissuade even more people from voluntarily remitting what they owe. The IRS chased down more than $100 billion of unpaid tax bills in the year ending September 30, 2023, and $32 billion extra following audits.Corporate attorneys are also preparing for less enforcement activity and smaller fines from the Securities and Exchange Commission. Under Acting Chair Mark Uyeda, the agency already has dropped investigations and cases against cryptocurrency exchanges and disbanded a team devoted to such markets, despite Chainalysis estimates that about $180 billion of digital tokens have been used for illegal activity over the past five years.The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is also being left for dead, even after recovering about $20 billion for customers and collecting $5 billion in civil penalties since 2012. Acting head Russ Vought in February ordered the independent agency to stop all work.Despite this onslaught, U.S. companies are unlikely to embark on a crime spree. High-powered law firms have cautioned against any overtly bad behavior, reminding clients that they remain susceptible to investigations. “While the Trump administration’s enforcement strategies represent a dramatic break from the past, it is critical to emphasize that these changes reflect how the laws will be enforced and not changes to the underlying laws themselves,” corporate law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz wrote recently.The president’s freewheeling ethos could easily seep into boardrooms anyway. CEOs are already struggling with White House tariff policies and fears of an economic downturn. If the risks of official investigation are lower, compliance departments may become convenient places to cut costs. If executives responsible for ensuring rules are followed turn their attention elsewhere, they could create an atmosphere more susceptible to slipshod work and rogue behavior.Other insidious effects are possible, too. White-collar crime is typically associated with Wall Street fraudsters like Bernie Madoff and high-level managers at multinational companies, including Enron’s Ken Lay. But women and Black men are more apt to be prosecuted for financial crimes than any other gender or racial group, echoing inequalities throughout the U.S. judicial system, according to an analysis of 2 million federal criminal cases published by the Southern California Law Review.More broadly, higher rates of corruption tend to erode a country’s economic growth and investment, studies have found over the years. It can distort how governments spend money, starving projects that would benefit bigger clusters of society in favor of ones where extortion is easier. Skewed financial incentives also have a way of luring smart people away from more useful and productive jobs.In the early 2000s, a slew of accounting and embezzlement scandals involving industrial conglomerate Tyco, telecom titan WorldCom and others led to a sharp tightening of corporate compliance systems. The resulting investment in monitoring and record-keeping should be an important, albeit limited, stopgap against a return of widespread misconduct. Even so, ignoring white-collar crime will leave plenty of fresh illegality for future prosecutors to uncover, assuming a stricter administration returns someday.Follow @jgfarb on X